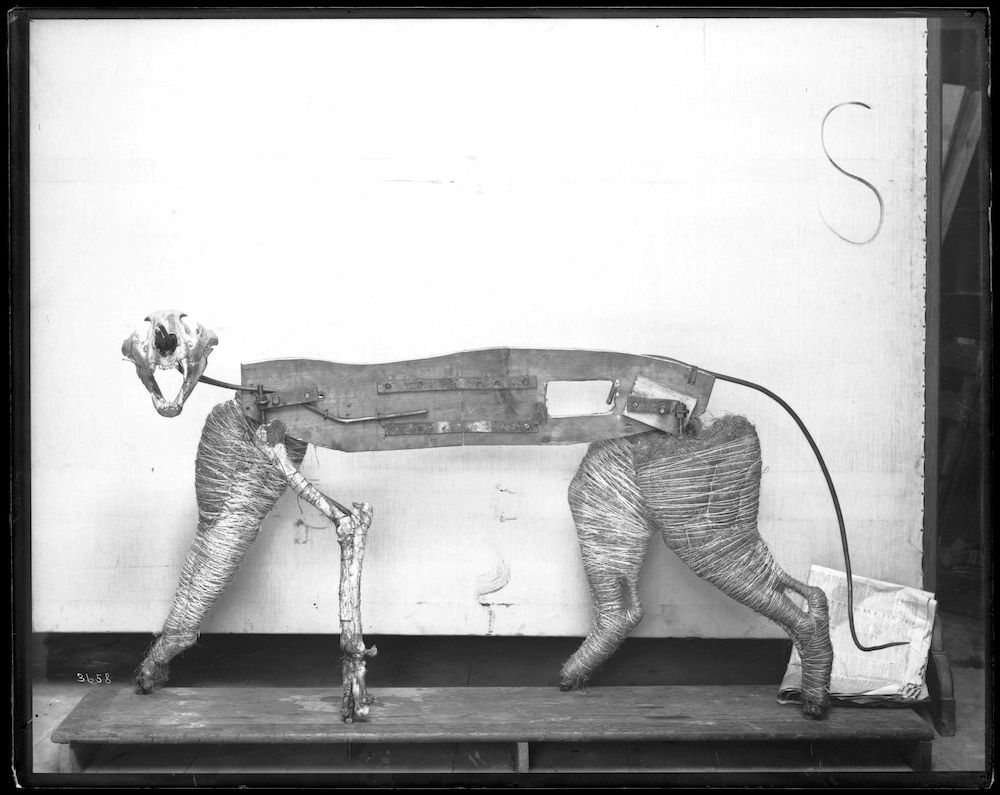

Unnatural nature

I want to be clear. I’m interested in nature—but not the so-called natural.

I want to be clear. I’m interested in nature—but not the so-called natural.

This word has been co-opted by those who think they know what nature is: It’s the way things are or have been within recent memory. It’s men who are men who love women who are women. It’s products made from plants rather than technology. But I have no desire to return to an idealized past, coerce conformation with a narrow set of norms, or sell greenwashed products.

The ideal of the natural has great power over us. We want to do what is natural. So it’s easy to misconstrue the natural. Or to outright misuse it. That’s why we need to question our terms, to help us cut through confusion and clutter and get to a better, clearer starting place for this project of trying to find our human place amongst nature.

When I encounter nature, I’m often surprised at the ways it defies expectations established by the human construction of the natural. When observed with fresh eyes, nature becomes unnatural. Seabirds mate for life, with birds of both sexes sharing equally in parental care. Microscopic single-celled organisms exchange essential nutrients with others that can’t produce them, cooperating to survive. Whales share songs and dolphins learn hunting techniques in ways that mirror how humans transmit bits of our own culture.

For many, division of labor based on sex, competition between species, and the special status of humans above all creatures are presumed to be natural, unquestioned defaults. But the unnatural natural world suggests alternatives to us.

I’m intrigued by these alternatives. They spark my imagination and give me hope that our human society could be different. If equality’s for the birds, why can’t it also be for us? If microbes can cooperate and thrive, why can’t we? If whales and dolphins have culture just as humans do, perhaps it’s possible to be civilized without being cutthroat.

Part of questioning the power of the natural is not only questioning the meaning of the word, but our deference to the concept. An observation of a pattern is no obligation to extend the sequence. Humans often, for example, choose not to eat meat, though it’s a traditional source of nutrition for many human groups and a common food for many carnivorous and omnivorous species. So I see no reason why the natural must be mandatory, though I suspect the natural is more expansive than we’ve imagined.

Might an unnatural nature be a more humane nature? Perhaps there are still lessons we can learn from the natural world. I plan to explore a few through this series of letters. But let’s begin by discarding the baggage of the natural—the phony pastoral past, fabricated sexual roles, and mendacious marketing messages—so we can perhaps better situate the human within the natural.